"Let's hallucinate together" and 4 other lessons from dungeon masters

A well-run game of dungeons and dragons is a playbook for building a thriving community.

We recently had the pleasure of sitting down with Josh Selesnick, professional Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) dungeon master and team builder, to chat about his use of D&D scenarios to build team morale, work through interpersonal issues, and develop team chemistry.

Here are five lessons you should take away from this topic:

1. Facilitate: Don’t control the experience

The dungeon master’s job is to create the world that the adventurers are playing in - much like it’s the community manager’s job to create the environment that the members are interacting in. That doesn’t mean that the DM controls the actions and outcomes of the game. The DM is there to give the players context, guardrails, and opportunities. It’s ultimately up to the players to make decisions and choose to take action (or not) when encountering a new challenge or opportunity.

As you think about designing the world your members will be “playing” in, consider how restrictive your mindset (and corresponding rules) is with regards to the behaviors you’ll tolerate and opportunities you’ll offer. Write policies and guidelines when and where they are needed to prevent harm. Design your member journey as an open world map where members can choose their own adventure. Along the way, each member will have their own experience, encounter their own monsters, and roll their own dice. Your job isn’t to overcome challenges for them, but to make sure that they have what they need to succeed.

2. Incentivize by design

The dungeon master’s role is to design rewards that adventurers can earn by making good decisions. The community manager’s role is to give members the opportunity to participate and engage in ways that are interesting and valuable to them - and to reward smart actions and good decision-making by members. With this in mind, choose wisely when considering which programs you offer and the metrics you choose to measure success by.

(Oh, come on…y’all knew I was gonna weave metrics in here somewhere…)

In addition to designing to incentivize desired behaviors from your members, incentivize yourself and your team to prioritize work that builds towards your ideal experience, rather than becoming distracted by vanity metrics like engagement. Measuring “engagement,” however you define that term, can lead you down a path towards a treasure room full of fairy gold. Engagement, after all, could be either positive or negative, and can be easily manipulated in the short term by artificial inflation or seasonal fluctuations. Engagement for the sake of engagement is an exercise in puppet theater and has no actual impact on the business’ bottom line on its own.

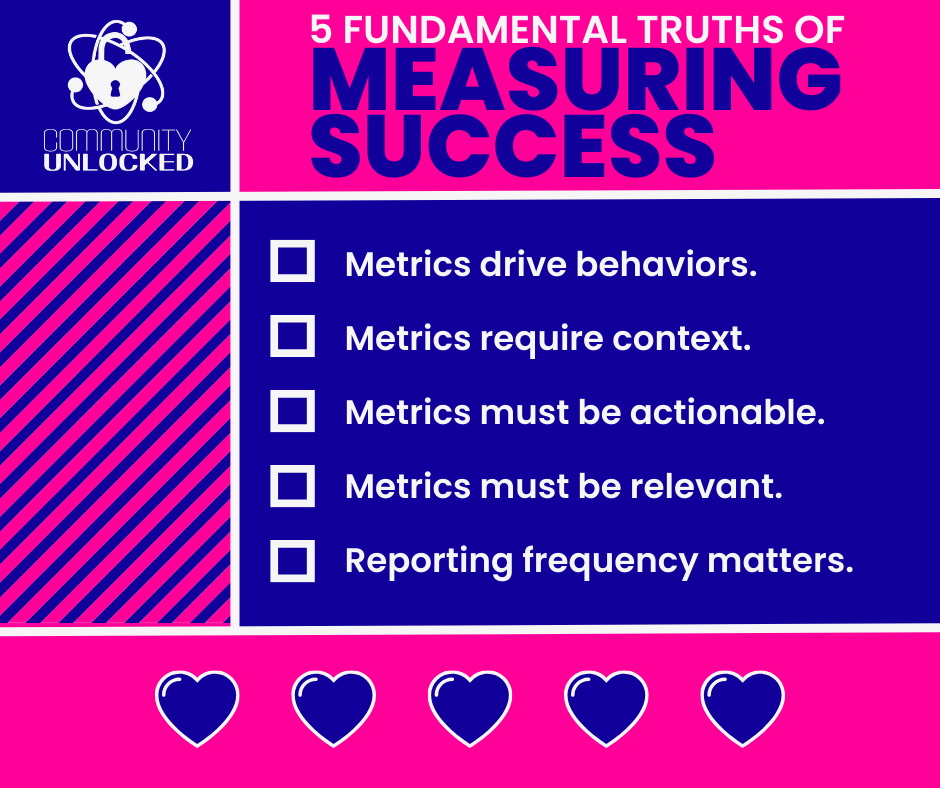

Instead, consider the following fundamental truths of setting good success metrics.

Set metrics that incentivize the behaviors that you want to see - both by your members and your team.

As we heard from our guest, Sheeri Cabral, in a recent episode on the podcast, metrics are merely the beginning of the story. To be informational, interpretation of data requires you to ask questions. I find that ratios, which convey a relationship between two numbers, tend to give more contextual information than nominal measures.

When you create your success metrics, you should have a clear understanding of what you want them to do and what factors might influence them. Commit only to success metrics that you can influence directly and significantly. Metrics must be actionable, which means that when a metric doesn’t do what you want or expect it to do, you should already know what you will do about it.

Your metrics must be relevant to you, your team, and the business. They must also impact things that are relevant to your members; otherwise, you’ll find that you and your members have chosen divergent paths down the road, with you working towards different objectives and even, at times, working against each other.

Reporting too (in)frequently on metrics can affect how the data is interpreted. Think of it like zooming in or out on a window of time. If you look at data too closely, you lose the context of patterns over time. If you wait too long to report on the same data, you’ll miss the opportunity to act in response to the information.

For example, knowing how many new members joined your community this month is nice to know but doesn’t really help without knowing other figures, like:

How many total members do you already have?

How many members joined last month?

How many joined this time last year?

With the context of trends over time, you can determine if this is an expected result, a disappointing result, or a pleasant surprise. If there’s an issue impacting the ability of members to register for the community, you’ll be able to respond to it in a timely manner by reporting on the data at least once a month. But, if you report on the data once a day, you’ll likely miss the red flags of lagging aggregate member growth over the month.

Reporting frequency matters.

3. Invite vulnerability by being vulnerable

In order to facilitate a game like D&D that doesn’t have any visual cues (unless you are using a dungeon map and tokens, but that’s primarily just to keep everyone aligned on your relative location in the dungeon), there is an element of group imagination required. As Josh says in my favorite quote of the episode, “Do you want to hallucinate a story with me for like an hour an a half?” He goes on to explain that willingness to make a fool of yourself is sometimes required in order to help people overcome the skepticism, resistance, and reluctance that they might bring to the game. Part of that dynamic can include calling out the shared absurdity of the situation sometimes. If we can all acknowledge that this is silly and we’re doing it any way, people feel less resistant to being silly themselves.

Psychological safety is a topic I’ve spoken and written about at length in the past and it’s something that most community builders understand intuitively. While we know this is important, psychological safety is still noted by many as the reason why they choose not to engage in a space.

A key component of community is the exchange of value (which I wrote about recently), which can only happen when members feel safe to speak up about their needs. To admit that you need something is, in itself, an act of vulnerability. The follow up question becomes “what do you have to offer in exchange?” which can be an uncomfortable question to think about - especially for anyone who is new to the experience or who is already dealing with imposter syndrome.

4. Celebrate (and mourn) together

Dungeons and Dragons is a game that deals with permanent death of characters who fail to overcome challenges they face. One failed roll of the dice can lead to the elimination of a character who has been a part of a team of adventurers for real world years. Players become emotionally invested in the well-being of each other’s character avatars, and feel genuine joy when they succeed and grief when they die.

Building a community, especially one that spans the globe, can feel at times just as ethereal as a D&D dungeon, and other times as real as the friendships we form in our day-to-day lives. How is it possible that we are able to build such deep relationships with people who we have either never met in person, or who we see so infrequently that it may be years between visits? By sharing the experiences of wins and losses, success and failure, and by being mutually invested in each other, people develop deeper bonds than might seem possible.

I, for one, met my first husband playing World of Warcraft. Many of my closest friends are ones that I’ve only seen in person a handful of times - if at all. I’ve worked for managers who I hadn’t met in person for over a year - if at all. As community managers, it’s our job to help the business to understand that the power of community comes from deeper bonds than customer enablement, and to help the community to understand that we want our relationship with and between them to be more than transactional. (Look for a separate blog post coming soon on this topic…)

5. Help people find roles that fit their strengths

People want to succeed. In this episode, we talked a bit about personality types and I laughingly asked Josh if there are personality profiles that typically fit classes in D&D. He mentioned that rogues and wizards tend to be chosen by more introverted people, while classes like bards might be more commonly chosen by extroverted people. Acknowledging that people have different strengths and preferences is the first step in helping them to be their best selves.

As a community builder, your job is not to form people into “ideal community members.” Like a dungeon master, your job is to help your dungeon party be successful and achieve their mutual and personal goals. After all, you can’t make everyone be a nice person, but you can help them identify and own their strengths and make the choices that suit their alignment, allowing them to contribute in ways that feel good for them and help the team overall.

Happy raiding, dungeon masters! Your favorite chaotic good-oriented salty avocado.

Listen to the entire episode here:

Episode 8: Community and Gaming

The team explores the team building power of games, like Dungeons and Dragons with professional dungeon master, Joshua Selesnick.

And don’t forget to subscribe to get all the future episodes and editions of this newsletter delivered directly to your inbox!

I’m thrilled to share that I am speaking at the 2024 Learning and HR Tech Solutions Conference in April! I’ll be speaking on the power of community and mentoring to support learning outcomes at scale. If you’re interested in attending, you can register at learninghrtech.com.

Great article, Jamie! As community builders, we need to look at adjacent social spaces and how to apply the lessons from them to the work we do. Also, as you know, I'm a huge Josh fan.