Your goals are a pile of rocks. (a.k.a. 3 hard truths about measuring your community impact)

Your community team likely struggles with unclear goals and objectives. They probably spend way too much time defending their jobs and arguing about priorities with skeptical stakeholders, and not enough time actually doing the work. This misalignment of productivity for community managers not only causes the company to lose time and miss opportunities; it creates resentment, conflict, and ultimately, burnout. It's hard for executive sponsors to defend the investment in the community when we are unclear with the value that we are providing to the business. So, we pick and choose vanity metrics to show that we're "making progress." (Progress towards what? No one can say.)

In response to this problem, an incredible amount of content is built with the intention of helping community managers learn how to justify the investment in community for the business. Just do a quick Google search on "business value of community." Go on. I'll wait.

I've come to the conclusion that we are collectively struggling with this existential crisis for three core reasons:

(1) Executives and managers are ineffective at setting goals and using performance management frameworks.

(2) Community doesn't need a new methodology to show value.

(3) Community is a means, not an end.

Truth #1 - Everyone is bad at OKRs.

Management science has long been fascinated with the idea of tangible, measurable goals as a means for evaluating performance, effectiveness, and efficiency in every workplace function. Whether your organization uses Andy Grove's OKRs (Objectives and Key Results), their predecessor, Peter Drucker's MBOs (Management by Objectives), SMART goals, or KPIs (key performance indicators), you've more than likely engaged in some practice of professional goal-setting based around measurable outcomes – and endured the subsequent measurement of your value based on your performance against these metrics.

Most leaders don't know how to build OKRs.

I have a long-standing love-hate relationship with OKRs in that they add clarity and cohesion when done well; but they are rarely done well. Overly complicated goal setting processes waste time and add complexity where there doesn't need to be any.

OKRs should directly connect work tasks with business priorities. Done well, OKRs can:

- reinforce an individual's buy-in to their work and the company

- facilitate cross-team collaboration

- reduce inefficiency and redundancy

- reduce time to achieving results

The organization becomes truly greater than the sum of its parts.

Indicators of a poorly aligned OKRs and goal-setting processes are:

- individuals can't explain how their work contributes to the overall organizational goals

- team members are not energized by achieving or exceeding company goals

- "I inherited this when someone left," or "because it's best practice," or "it's industry standard," or my least favorite, "because it's how we've always done it."

- organizational goals like "have all our goals finalize by end of month and submitted in the system" exist

I'm guessing that right now your team is spending time preparing reports and slide decks for company-wide meetings in which they explain their performance against goals and everyone in the room collectively nods their heads and says, "hmm...mmhmm..." even though no one has any clue why we should care about how many questions were asked in the forums or how many people showed up to a webinar or how many total likes were received in a given period but no one wants to say it out loud so we all just pretend like we know what's going and really someone should be asking "why the hell do I care about this? how does this impact our bottom line?" but we're all being too polite until the pink slips come out and suddenly the entire industry collapses...

...but I digress.

Measuring something doesn't make it worth measuring. Data is not intelligence. Say it with me. Data. Is. Not. Intelligence.

Truth #2 - Community goals are not unique.

So, that brings us to how to set goals the right way. I could not give any lets shits about which goal-setting framework you use as long as you use it properly.

Community goals should always be a derivative of the company goals - just like every other functional area. The thing that makes community goal-setting complex is the lead time required to see results. Unlike marketing campaigns, which are often time-boxed to, at most, 3-6 months long, community impact may not be seen for 12-18 months. And, let's be honest - the business world runs around finance and tax timelines. This is why quarters are the standard unit of measure, and why fiscal years dictate goals, budgets, and ultimately, day-to-day work.

When the executive team exerts pressure on the community team to show 3-6 month results that indicate that they are on-track to achieve their year-long goals, we end up with "leading indicators" like "engagement rate" and "community growth." These functional, tactical measures are fine for gauging the health of the community, but the reality is that they do not, in any way, communicate the value of the community to the business.

Truth #3 - Community is a tool, not an end state.

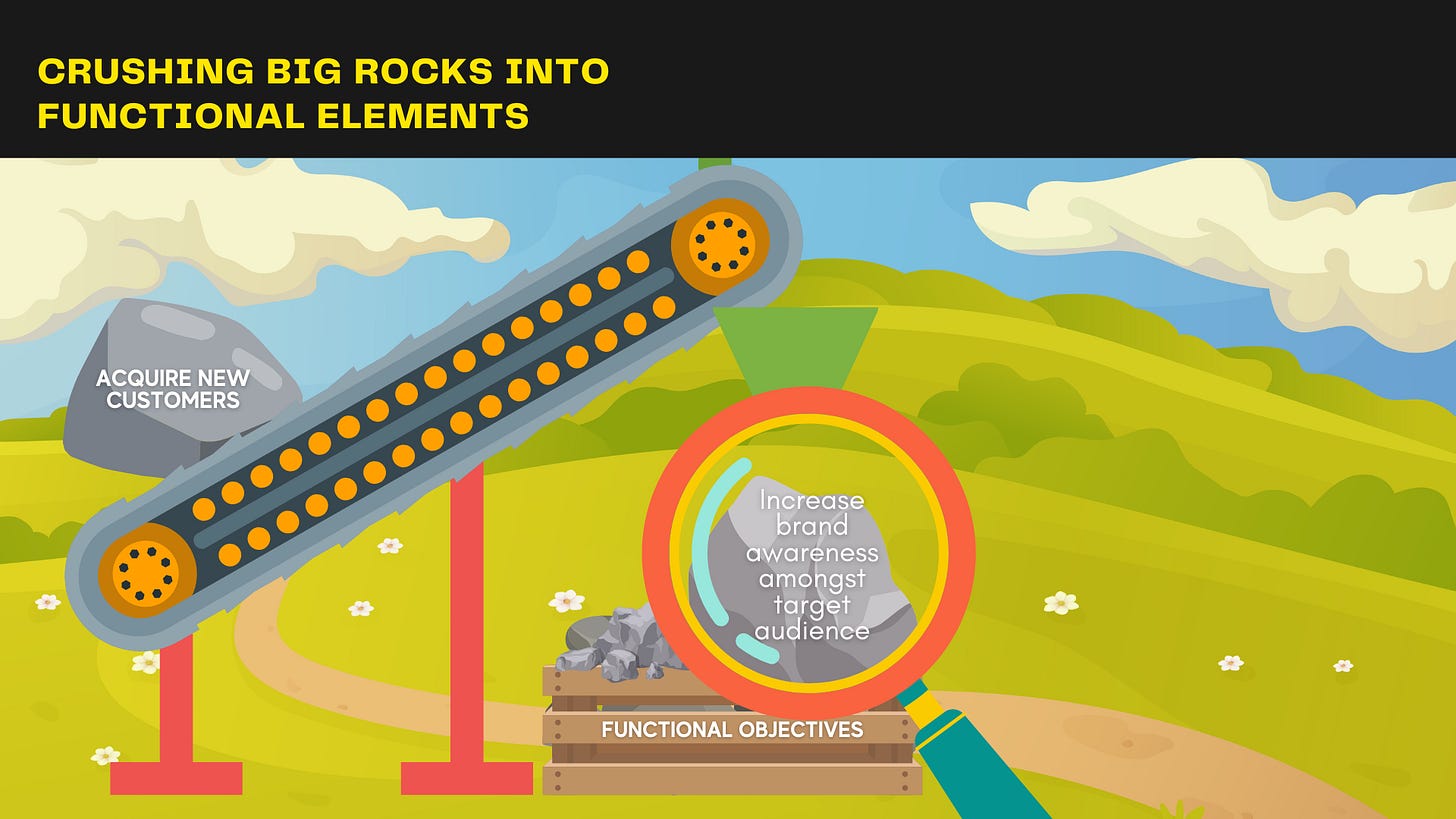

I once sat through an All-Hands meeting with a CMO outlining the "big rocks" for the year and when I saw this slide,* I died inside.

Community is a tool, not an end state.

The ideal state for a community program is sitting neatly within one or more areas of focus for the company. Instead of creating a community (for "reasons") and trying to later figure out where it fits into the organization, you should first be very very clear on your answer to this question.

Why do you think you need to build a community?

There is no right answer to this question other than what is right for your company at this point in time. Community can be a hammer, a wrench, a level, a measuring tape, or a saw, depending on the project you're trying to build, fix, or measure.

Example: Growth Stage SaaS Tech Startup

For a company heavily focused on growth (new customer acquisition and/or customer growth), the community could be deployed to support that growth. From a goal-setting perspective, we should start with the growth goal itself. For the company, the overarching goal might be to increase ARR by 50%. The next question to answer is:

How do we increase ARR?

Well, we basically have two options: (1) acquire new customers; or (2) increase the value of our current customer contracts.

Now, we are looking at a pile of key results that, when we apply numbers to them, are measured based on the performance of anywhere from one to six teams, depending on the size of the organization.

Obviously, there are more elements to the top level goal of increasing the ARR of the company than just brand awareness, but if you were to blow out this model to encompass the entire company, you can see how each team contributes to the same small set of goals.

What are you trying to accomplish?

Instead of everyone hauling their spreadsheets to the QBR and putting the entire company to sleep by dumping their Big Rocks in a pile and trying to sort out the value, every initiative for every team should build up to the company's top goals.

Remember that the key to success here is in ensuring that the people looking at a particular level of goals have the context to actually understand what you're showing them. Otherwise, you're creating a positive signal without a matching receiver. You may be able to read into the trends and emerging signals from your data, but chances are, your CEO sees "green arrow goes up = good" or "red arrow goes down = bad." This translates into frustration on both sides. You don't understand why you aren't getting the support you need when you ask for budget, resources, or time. The CEO doesn't understand why they keep throwing money at this program. You end up re-explaining and defending your purpose month-after-month, quarter-after-quarter.

In my next post, you'll find a 5-step guide to goal-setting that I hope will simplify this process for you and your teams.

Stay salty, friends.